Heather Cox Richardson

Everyone knows the iconic image of John, Paul, George, and Ringo from the cover of Abbey Road. That image launched deep investigations into its hidden meanings—“Paul is Dead,” anyone?—and into the stories it might be telling about the Beatles.

investigations into its hidden meanings—“Paul is Dead,” anyone?—and into the stories it might be telling about the Beatles.

There was a story behind the image, too, and it’s one in which art and history intersect. As with any photo shoot, at the August 1969 session with the Beatles, the photographer Iain Macmillan took a number of different shots. They swept in bystanders, cars, different expressions on the musicians’ faces, different interactions.

What can these photos tell us about history?

I wonder, not only because it’s Friday, but because of another treasure trove of images recently discovered in Chicago. Vivian Maier was an emigrant from France in the 1930s and worked as a child in a New York sweatshop. When she was older, she worked as a nanny in Chicago. She had few friends, apparently, and interacted with the world largely through her camera. She left her photos, largely unseen, in a storage locker in Chicago, which put them up for sale when her payments became overdue after her death. John Maloof, writing an Images of America book about a Chicago neighborhood, bought them.

left her photos, largely unseen, in a storage locker in Chicago, which put them up for sale when her payments became overdue after her death. John Maloof, writing an Images of America book about a Chicago neighborhood, bought them.

What he found was, to my mind, incredible. These are simply stunning pieces of art, chronicling the world of the streets in Chicago, primarily, as well as New York and distant countries. Her use of line, light, and texture is extraordinary.

Her photos are works of art, but they are also unusual snapshots of life in the mid-twentieth century. What can they tell us about the world in her era?

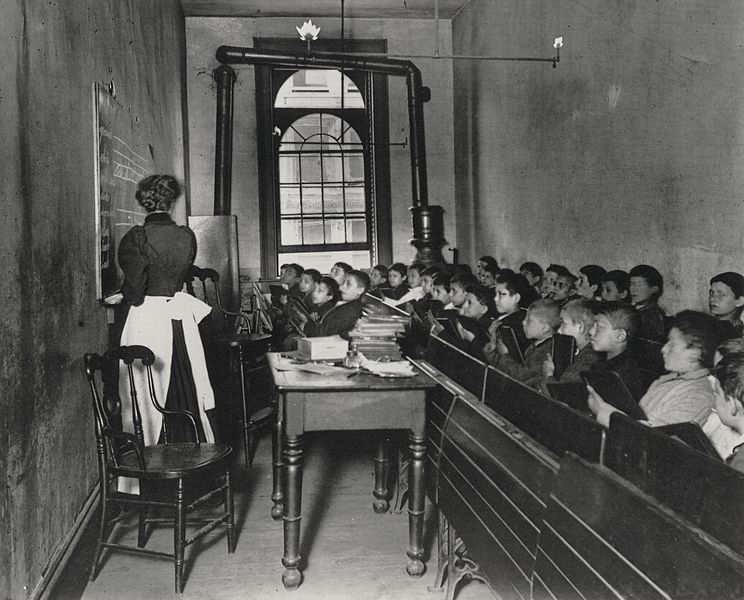

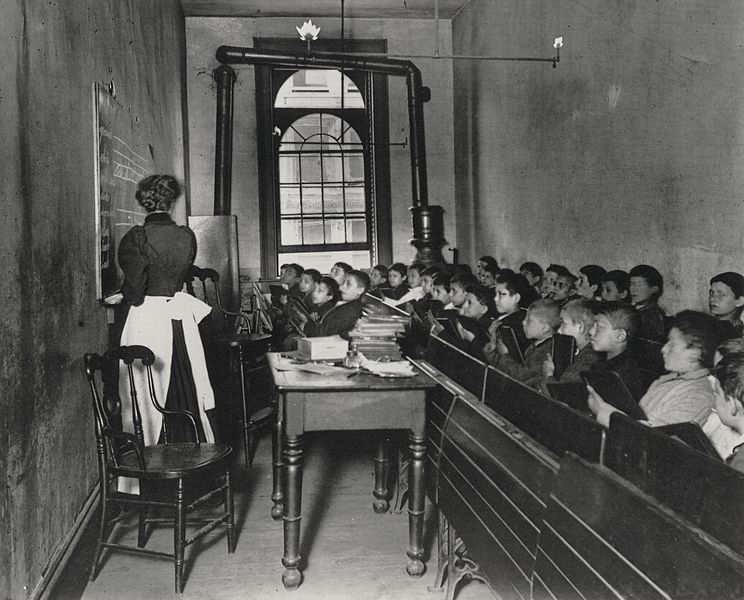

The historical reading of photographs intended to tell a societal story is straightforward compared to reading the Abbey Road photos or the Vivian Maier collection. Jacob Riis was making a point about urban poverty; Nick Ut was making a point about the Vietnam War with his 1972 image of Kim Phuc. A recent article honoring the late Tim Hetherington suggested that the key to successful war photography was an understanding of the complexity of the conflict and the ability to capture images encapsulating that story.

straightforward compared to reading the Abbey Road photos or the Vivian Maier collection. Jacob Riis was making a point about urban poverty; Nick Ut was making a point about the Vietnam War with his 1972 image of Kim Phuc. A recent article honoring the late Tim Hetherington suggested that the key to successful war photography was an understanding of the complexity of the conflict and the ability to capture images encapsulating that story.

Artists, of course, have a different imperative. Their stories are not, necessarily, driven by current societal concerns. But if art historians can use paintings to interpret the world in which the images were made, shouldn’t historians be able to use artistic photography to interpret the modern world? And if so, how?

What can the Abbey Road photos tell us about their era?

Everyone knows the iconic image of John, Paul, George, and Ringo from the cover of Abbey Road. That image launched deep

investigations into its hidden meanings—“Paul is Dead,” anyone?—and into the stories it might be telling about the Beatles.

investigations into its hidden meanings—“Paul is Dead,” anyone?—and into the stories it might be telling about the Beatles.There was a story behind the image, too, and it’s one in which art and history intersect. As with any photo shoot, at the August 1969 session with the Beatles, the photographer Iain Macmillan took a number of different shots. They swept in bystanders, cars, different expressions on the musicians’ faces, different interactions.

What can these photos tell us about history?

I wonder, not only because it’s Friday, but because of another treasure trove of images recently discovered in Chicago. Vivian Maier was an emigrant from France in the 1930s and worked as a child in a New York sweatshop. When she was older, she worked as a nanny in Chicago. She had few friends, apparently, and interacted with the world largely through her camera. She

left her photos, largely unseen, in a storage locker in Chicago, which put them up for sale when her payments became overdue after her death. John Maloof, writing an Images of America book about a Chicago neighborhood, bought them.

left her photos, largely unseen, in a storage locker in Chicago, which put them up for sale when her payments became overdue after her death. John Maloof, writing an Images of America book about a Chicago neighborhood, bought them.What he found was, to my mind, incredible. These are simply stunning pieces of art, chronicling the world of the streets in Chicago, primarily, as well as New York and distant countries. Her use of line, light, and texture is extraordinary.

Her photos are works of art, but they are also unusual snapshots of life in the mid-twentieth century. What can they tell us about the world in her era?

The historical reading of photographs intended to tell a societal story is

straightforward compared to reading the Abbey Road photos or the Vivian Maier collection. Jacob Riis was making a point about urban poverty; Nick Ut was making a point about the Vietnam War with his 1972 image of Kim Phuc. A recent article honoring the late Tim Hetherington suggested that the key to successful war photography was an understanding of the complexity of the conflict and the ability to capture images encapsulating that story.

straightforward compared to reading the Abbey Road photos or the Vivian Maier collection. Jacob Riis was making a point about urban poverty; Nick Ut was making a point about the Vietnam War with his 1972 image of Kim Phuc. A recent article honoring the late Tim Hetherington suggested that the key to successful war photography was an understanding of the complexity of the conflict and the ability to capture images encapsulating that story.Artists, of course, have a different imperative. Their stories are not, necessarily, driven by current societal concerns. But if art historians can use paintings to interpret the world in which the images were made, shouldn’t historians be able to use artistic photography to interpret the modern world? And if so, how?

What can the Abbey Road photos tell us about their era?