.

The following guest post come from Randall Foote. This is part of an exchange he had with the eminent historian John Lukacs about the usefulness of the idea of "prehistory." See Foote's earlier post on a related topic here. Foote is retired from his business and now teaches as an adjunct instructor at Roxbury Community College.

Dear Professor Lukacs,

As to your question:

“. . . . Because of your thoughts about the genesis of mankind: do you agree with Barfield (and myself) that, strictly speaking or, rather, thinking, there was no such thing as ‘prehistoric’ man?”

‘prehistoric’ man?”

Yes, that goes to the heart of one subject I am working on.

In brief: no, the idea of “prehistoric man” makes no sense to me, in either of the two ways in which it is understood. The sense of “pre-history” as that which comes before written history is very odd, as if the discovery and use of writing were some particular defining moment in human evolution, rather than merely one means by which we understand the present and the past: Man’s past defined solely by our own current means of comprehending it. This concept leads, for example, to a belief that the early Romans were a “historic civilization”, while their neighbors the Celts were a “prehistoric” archaeological Culture-type, who only entered into “History” when Caesar wrote about them in his Commentaries? All that changed was the historical tools by which we can learn about them. It is not difficult to trace these newly “historicized” Celts back to the Hallstatt culture of Central Europe, it merely requires different tools than reading primary sources. And these are similar to the tools that we might use to understand the daily lives of non-literate peasants of medieval Europe – the “testimony of the spade” (pace Bibby).

The broader sense of “prehistoric” is as that time before, for example, the Neolithic Revolution – which actually was a type of defining moment in certain parts of the human world. I would instead use the term “Archaic Man” for this. For me, and I believe for you and for Barfield, there is only one defining moment in the History of Man: which is when human consciousness and human language began, when the Word took human form in some mysterious manner. This may have happened in an instant or it may have been something that occurred over a few generations, but this essential change is not something that “evolved” over a million years in some Darwinian process from hominoids and hominids.

There was time and a place when human history truly began: perhaps 100,000 years ago in the northeast of Africa. A spark went into a physical body that then became Man. God breathed a soul into Adam’s nostrils. Spirit became matter, brain became mind, as consciousness and language were born for the first time. The mechanism for this change in consciousness is not understood yet. Perhaps it is an unknowable Act of God, as the cosmological Big Bang will ever be unknowable, the first moment of Creation.

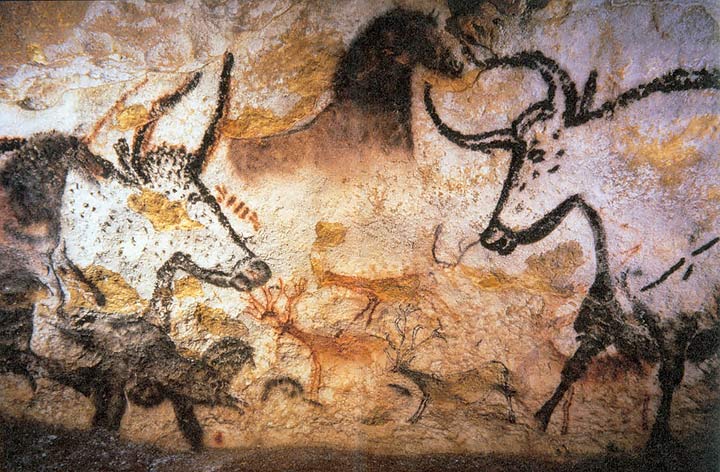

But just as physics can trace the path back to almost the first moment of the Big Bang, so too can linguistics, genetics and anthropology point roughly to the conception of Man as a conscious being. Language families (and macro-families) converge at some point in the past, pointing to one original language; there still exist traces in the most unrelated of languages of common words for the simplest of things (finger, one, two, eye). In addition, unique elements of human genetic material also converge back in time, circa 100,000 years ago. Further, a modern physical form of Man emerged out of Africa into the Middle East about 80,000 years ago. With this new human (“anatomically modern homo sapiens” in anthropology) is found evidence of burial, symbolic expression (“art”), and apparently unnecessary and changing elements of design in tools and clothing (“fashion”), among other differences from earlier hominids (Neandertal, Erectus, etc.). And the other, older hominids soon vanished before the newcomer, for whatever reason. Human history began as man became fruitful and multiplied, out of Africa and across the earth.

I am only able to understand this and other evidence as pointing to the inception of human language and human consciousness, which define Man (in the image of God). In the beginning was the Word. There does not seem to be any gradual Darwinian “evolution” leading up to this beginning of human culture, of humanity itself (as opposed to the evolution of the hominid body), nor any radical change since that time.

Of course, human culture has evolved over the millennia, just as the understanding of God has evolved, but human Language (as distinct from all the supposed animal “languages”) either is or it is not, across the races of man as well as in the growth of a child. There are no “primitive” or unformed or partial languages. The fact that any human infant can learn any human language fluently argues convincingly for the monogenesis of language, with no significant/essential changes having occurred since that genesis. Evolution of language (as in Barfield) is cultural refinement, not essential change, as is “the evolution of consciousness, which is probably the only evolution there is” (End of an Age). (vide Lincoln: “The only progress is of the human heart”). Human consciousness begins with language, and since that point “evolution” might be refinement and growth, but not a change-of-state.

Perhaps much as you found correspondences to your own historical thinking in Heisenberg’s writings, I have been working to connect science and linguistics (not a science) to my own historical sense of human beginnings. This sense, this human story, is not Darwinian or “scientific”, nor in a strict sense religious--but human, historical, including and larger than science and religion. Currently, science and religion are each devolving into their own forms of fundamentalism, and the time is past when either can alone provide the needed understanding of man’s “evolution” (or of the universe for that matter). I see this “historical Genesis” as the opening chapter of the new kind of history, as that you call for, a history for a new era, following upon a “conscious historical recognition of the opening of a new phase in the evolution of our consciousness.” ( JL, Confessions of an Original Sinner.)

The following guest post come from Randall Foote. This is part of an exchange he had with the eminent historian John Lukacs about the usefulness of the idea of "prehistory." See Foote's earlier post on a related topic here. Foote is retired from his business and now teaches as an adjunct instructor at Roxbury Community College.

Dear Professor Lukacs,

As to your question:

“. . . . Because of your thoughts about the genesis of mankind: do you agree with Barfield (and myself) that, strictly speaking or, rather, thinking, there was no such thing as

‘prehistoric’ man?”

‘prehistoric’ man?”Yes, that goes to the heart of one subject I am working on.

In brief: no, the idea of “prehistoric man” makes no sense to me, in either of the two ways in which it is understood. The sense of “pre-history” as that which comes before written history is very odd, as if the discovery and use of writing were some particular defining moment in human evolution, rather than merely one means by which we understand the present and the past: Man’s past defined solely by our own current means of comprehending it. This concept leads, for example, to a belief that the early Romans were a “historic civilization”, while their neighbors the Celts were a “prehistoric” archaeological Culture-type, who only entered into “History” when Caesar wrote about them in his Commentaries? All that changed was the historical tools by which we can learn about them. It is not difficult to trace these newly “historicized” Celts back to the Hallstatt culture of Central Europe, it merely requires different tools than reading primary sources. And these are similar to the tools that we might use to understand the daily lives of non-literate peasants of medieval Europe – the “testimony of the spade” (pace Bibby).

The broader sense of “prehistoric” is as that time before, for example, the Neolithic Revolution – which actually was a type of defining moment in certain parts of the human world. I would instead use the term “Archaic Man” for this. For me, and I believe for you and for Barfield, there is only one defining moment in the History of Man: which is when human consciousness and human language began, when the Word took human form in some mysterious manner. This may have happened in an instant or it may have been something that occurred over a few generations, but this essential change is not something that “evolved” over a million years in some Darwinian process from hominoids and hominids.

There was time and a place when human history truly began: perhaps 100,000 years ago in the northeast of Africa. A spark went into a physical body that then became Man. God breathed a soul into Adam’s nostrils. Spirit became matter, brain became mind, as consciousness and language were born for the first time. The mechanism for this change in consciousness is not understood yet. Perhaps it is an unknowable Act of God, as the cosmological Big Bang will ever be unknowable, the first moment of Creation.

But just as physics can trace the path back to almost the first moment of the Big Bang, so too can linguistics, genetics and anthropology point roughly to the conception of Man as a conscious being. Language families (and macro-families) converge at some point in the past, pointing to one original language; there still exist traces in the most unrelated of languages of common words for the simplest of things (finger, one, two, eye). In addition, unique elements of human genetic material also converge back in time, circa 100,000 years ago. Further, a modern physical form of Man emerged out of Africa into the Middle East about 80,000 years ago. With this new human (“anatomically modern homo sapiens” in anthropology) is found evidence of burial, symbolic expression (“art”), and apparently unnecessary and changing elements of design in tools and clothing (“fashion”), among other differences from earlier hominids (Neandertal, Erectus, etc.). And the other, older hominids soon vanished before the newcomer, for whatever reason. Human history began as man became fruitful and multiplied, out of Africa and across the earth.

I am only able to understand this and other evidence as pointing to the inception of human language and human consciousness, which define Man (in the image of God). In the beginning was the Word. There does not seem to be any gradual Darwinian “evolution” leading up to this beginning of human culture, of humanity itself (as opposed to the evolution of the hominid body), nor any radical change since that time.

Of course, human culture has evolved over the millennia, just as the understanding of God has evolved, but human Language (as distinct from all the supposed animal “languages”) either is or it is not, across the races of man as well as in the growth of a child. There are no “primitive” or unformed or partial languages. The fact that any human infant can learn any human language fluently argues convincingly for the monogenesis of language, with no significant/essential changes having occurred since that genesis. Evolution of language (as in Barfield) is cultural refinement, not essential change, as is “the evolution of consciousness, which is probably the only evolution there is” (End of an Age). (vide Lincoln: “The only progress is of the human heart”). Human consciousness begins with language, and since that point “evolution” might be refinement and growth, but not a change-of-state.

Perhaps much as you found correspondences to your own historical thinking in Heisenberg’s writings, I have been working to connect science and linguistics (not a science) to my own historical sense of human beginnings. This sense, this human story, is not Darwinian or “scientific”, nor in a strict sense religious--but human, historical, including and larger than science and religion. Currently, science and religion are each devolving into their own forms of fundamentalism, and the time is past when either can alone provide the needed understanding of man’s “evolution” (or of the universe for that matter). I see this “historical Genesis” as the opening chapter of the new kind of history, as that you call for, a history for a new era, following upon a “conscious historical recognition of the opening of a new phase in the evolution of our consciousness.” ( JL, Confessions of an Original Sinner.)