In a 1940s-style coffee stand in the middle of a drug store, six grey-haired gentlemen sit around a long, light-wood table sipping coffee and swapping stories. They’re here at 10am six days a week (Sunday is a church day, and the drug store, as with many businesses in the town, is closed then), and the

proprietor holds the same table for his most consistent patrons, who have gathered in this manner for over 25 years.

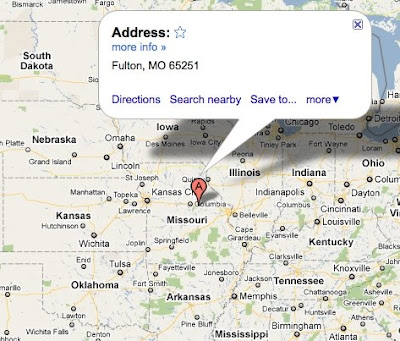

proprietor holds the same table for his most consistent patrons, who have gathered in this manner for over 25 years.Today’s topic of conversation is the day Winston Churchill came to tiny Fulton, MO, 65 years ago to the day. Fulton mayoral candidate Bob Craghead recalls his father charging out-of-towners a whopping 25 cents a pop to park at his farm just outside the city limits. O.T. Harris, whose family is a part owner of the Callaway County Bank across Court Street, is laughing as he recollects the bank’s CFO Tom Van Sant (a frequent visitor at Truman’s White House, and the man who encouraged Westminster College president Franc McCluer in his unlikely bid to bring Churchill to town) reputation as what Jerry Seinfeld called a “close talker.”

My pen is working overtime to scribble down these priceless recollections, in case the batteries in the voice recorder on the table betray me. In the weeks before my Fulton visit, I’ve had similar conversations, albeit by phone, with half a dozen Fultonians. One gentleman was so eager to share his memories that the aforementioned recorder ran to more than 90 minutes. Then he called back the next day with another half hour’s worth of vivid descriptions of the Missouri town as it was in the mid-1940s. I relished each word.

Certainly, oral histories can be distorted by forgetfulness, romanticism and exaggeration, but they remain an indispensable way for a historian (or any writer, for that matter) to add color and personality to his or her work. It is simple (and, sadly, the modus operandi for writers of history that’s as dry as a pile of October leaves) to read a couple of written sources and apply their

second-hand generalizations to a time and place. But to talk to people who were in the moment is to see what they saw, hear what they heard, touch what they touched. Such accounts also serve the purpose of putting events that fall into so-called “Great Man” history (in this case, Truman and Churchill parading through town and the latter then delivering his “Iron Curtain” speech) in the context of “regular” folks’ lives. It’s also all too easy to reflect on the impact of such an occurrence through other world leaders’ perspectives or with the benefit of hindsight, but to obtain the real reactions of people who were there adds a new dimension.

second-hand generalizations to a time and place. But to talk to people who were in the moment is to see what they saw, hear what they heard, touch what they touched. Such accounts also serve the purpose of putting events that fall into so-called “Great Man” history (in this case, Truman and Churchill parading through town and the latter then delivering his “Iron Curtain” speech) in the context of “regular” folks’ lives. It’s also all too easy to reflect on the impact of such an occurrence through other world leaders’ perspectives or with the benefit of hindsight, but to obtain the real reactions of people who were there adds a new dimension.Perhaps one reason certain writers avoid oral history is because it requires a different sort of effort. It can take weeks to track down people who were present at a particular event. Some writers surely think “who can effectively describe a bygone era.” You can have 10 conversations before you get one piece of usable information. In addition to prepping for the interview, jotting notes and/or recording, and transcribing, you need to cross-reference certain facts to verify authenticity, and to compare testimonies to establish sources.

And yet, even if it takes 10 hours of panning for every gold nugget minute, such treasures are hidden in the memories of people everywhere. Beyond the benefits of oral history for your project, there is the immeasurable value of creating connections and, if you’re fortunate, new friendships with your interviewees.

Then there is the time capsule bonus of recording first-person impressions for posterity. Recently, Frank W. Buckles, the last surviving American World War I veteran, passed away, marking the end for new oral histories of the Great War. The same will be true in just a few years for World War II, the Great Depression, and all sorts of other 20th-century subjects.

I feel fortunate to be speaking with these fine, 80-something individuals from Fulton while time remains.